November 2009 Archives

In the aftermath of Expozine, it turns out that I have some quite excellent overstock. Copies of Coping Mechanisms for the Young and Ambitious, as well as some fine postcards, are now available for your perusing and purchasing pleasure, on my Etsy page.

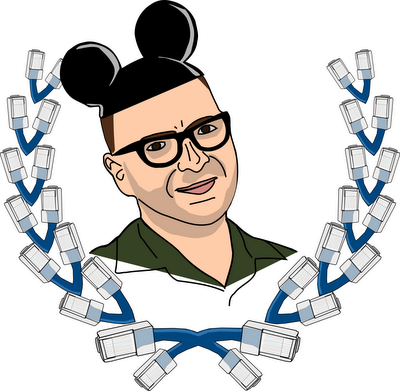

This is the last one, I promise. But I'm incredibly pleased with this illustration and article. The article, based on my interview with Cory Doctorow, appeared in this week's issue of The Link. It's called The Digital Backwater, referencing the sorry state of telecom policy and infrastructure in Canada. And here's the pretty picture that goes with it. The copy editor has dubbed the laurel the Wreathernet. This graphic is significantly bigger than the one on The Link's website, for your zooming pleasure. And, finally, if you want to see the article and graphic as they should be, check out the pdf of this issue.

It's a little dense, but it's complete. Below, the full transcript of my interview with Cory Doctorow.

12 November 2009

13h15ish to 13h40ish

GC: You said a few years back that you couldn't move back to Canada because of the bad internet

CD: It's getting pretty bad in England. It's certainly pretty bad here.

GC: The CRTC just came down with a ruling on traffic shaping...

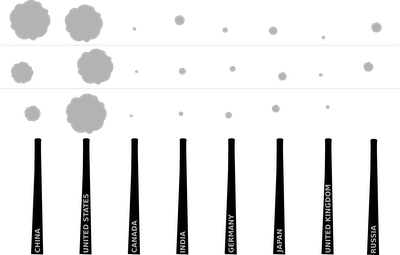

CD: Which was basically:you can only do terrible, immoral things in a limited way that we may police if we decide to. Yeah. It was a pretty awful ruling. I think the CRTC is generally asleep at the switch. I mean, the media consolidation in this country has been just disgraceful. So yeah, I'm pretty unimpressed with the CRTC as a regulator. The sheer amount of consolidation, both in media and telecoms and the cross consolidation between media and telecoms has been I think a total policy disaster for Canada. Canada's really lagging in the OECD in access, speed, cost and equality. They keep trying to redefine what broadband is in order to make us look better on the OECD stats. It's broadband if you can download a jpeg in less than a minute. This is not broadband. Broadband is Korean standard: 100MB. And up.

GC:Everyone's really proud of 21MB right now. On the whole 21MB thing, have you heard about this new thing Bell is doing? The turbostick? It's pretty awful. They're going for mobile internet, with a 500MB a month cap.

CD: I think the thing about caps is first of all, it's hard to imagine any other industrial sector that would say “there's a lot of demand for our product, how can we reduce it?” I think on the one hand, this represents a kind of failure of entrepreneurial imagination that's only possible where you have these monopolistic, badly regulated industries. The other thing about caps is what it does to network behaviour, network use. It punishes experimentation because you have to ration your network use. What this does is it undermines entrepreneurship. If you want to start a new Canadian networked business, your capacity to lure customers into your business is undermined by the fact that any customer who clicks on your web page will reduce their remaining bytes for the month. And bytes per month is a really hard measure for the average user, or even a sophisticated user to get their head around. Do you know how many bytes are in a web page before you click it? Or after you click it? We have a very hard time predicting the amount of bits that we have. So it's very hard to contain our use. So we would become even more conservative of our use. As a piece of national industrial policy, if you want to encourage the greatest amount of entrepreneurial activity on the network, the greatest amount of civic participation... Say you're planning for a pandemic swine flu outbreak and you want to produce a bunch of high quality health videos that will help people adequately prepare for the pandemic, do you really want people going “Well, I can spend my bits this month, my allowance, on looking at that health information, or I can spend it on downloading my banking information and I have to make that trade off, or I'm either going to get cut off or hit with some incredibly high overage fee.” Do you really want people making that decision? Is that good national policy? It would be different if the phone and cable companies were not subject to such enormous public subsidy. But they are. First of all, in the case of the phone companies, they got an enormous public subsidy in the fact that they exist at all. All that wire was laid with public expense. But everybody gets public subsidy in the use of the airwaves, in the use of rights of way, they essentially have de facto monopolies. I feel like the CRTC should say “If you don't want to allow a free and open network on these wires, that's your business. We'll either buy them from you at the scrap value of this copper, or you can take them out of our ground and we'll find someone else who'll run those wires. Somewhere out there, there's an entrepreneur who wants to provide the network that Canada deserves. If it's not you, that's fine. We'll have a competitive market. We'll have these guys who want to provide the network that Canadians want and you can provide the network that you think Canadians want. And if you're right and we're wrong, then Canadians will buy your service. But for so long as you're a regulatory monopoly, you have to act in the public interest.”

GC: Actually, how is it in the UK?

CD: It's not great. In general, the quality of governance in the UK is very poor. Partly because the political left has shifted so far to the right that there really isn't... I mean, I support the Lib Dems kind of generally because they're the only party that doesn't expect me to carry a biometric identity card. But as a left wing opposition goes, they're not very powerful and they're not very left wing. Labour, who are traditionally supposed to be the voice of the left, have shifted so far to the right that I think that they're... well... they're Bushites. Right? They went to war in Iraq. They are Bushites. Their policies are in line with those of George Bush. Including policies on civil liberties and so on. As a kind of microcosm of that, the network policy, the information policy is very poor. The government has been really reluctant to release information about its own operation. Quasi-governmental entities like the BBC are arguing for the right to put DRM on their broadcasts even though not only do they get public airwaves, but they get something like six or seven billion pounds a year out of the public's hands from the license fee, by governmental enforcement. It's really unseemly that they would argue for the right to DRM their signal. And now we have the copyright enforcement stuff. On one hand, you've got the anti-terrorism people saying that ISPs should be required to monitor and store all communications. That's also happening on the European level. Then you have the database nation where they're saying that we need, if not a national identity card, then a series of linked national databases that do the equivalent of a national identity card. And then finally, they're saying that we're going to have a three strikes regime where if anyone in your household is accused without evidence or conviction of three acts of copyright infringement you lose your network access and your name goes on a national register of people to whom it's illegal to supply internet access. This is really a dreadful piece of policy. I happen to live there and it's unlikely that I'm going to be moving away any time soon just for sheer inertia and the fact that my wife has a very good job, but they've got lots of network caps, they've got crummy networking policies. BT, who are the equivalent of Bell, really, in terms of being a legacy former national monopoly. BT got done for using something called Phorm, P-H-O-R-M, which I think may have had limited deployments here and in the U.S., I forget where. Initially, what they did was install Phorm as a piece of spyware on your computer without your permission. And what it did was inserted ads based on a tracking of every click you made on every page you visited. And then after they were told they can't install spyware on your computer without your knowledge, they went back and redid it as a piece of network middleware that tracks every click and does dynamic page rewriting again with these targeted ads. It's a revolting way of running a network. They're running it as an opt-out service. There's a huge amount of tracking that they're doing, a huge amount of monkeying with your network connection. It's very bad.

GC: You mentioned biometric ID cards. Of course, that's a pretty hot topic here right now because, of course, the border provinces need to comply with the U.S. Ontario is trying to roll out EDLs...

CD: Biometrics are an incredibly bad idea as a security measure. Partly because any good security token needs to be revokable in the event that it leaks. You need to be able to change your PIN if someone finds your PIN. You need to be able to get a new credit card number if your credit card number leaks onto the internet. What do you do if your finger prints leak? Right? And fingerprints leak like crazy. How many surfaces do you think you left your fingerprints on today? As a great example of this, the Chaos Computer Club lifted the fingerprints of the German chancellor, who was responsible for pushing for biometrics in that country, and made ten thousand copies of them on acetate, which would work in most fingerprint readers and widely distributed them. As a security metric, these are very very poor. And to the extent that we actually believe that we need security at the border, we should have good security, not bad security. That's one really important piece of it. But you know, the general linking of multiple databases, first of all, creates a false sense of security or certainty among the people who run those databases. There's a tendency to believe the database over reality. So if they say “well, the database says you were here and then here,” it's very hard to prove otherwise. The database becomes its own proof. And we know that those databases are very flawed and the more we link them, the more flawed they become. So there's that risk. In terms of Terry Gilliam's Brazil, it's the Tuttle-Buttle risk. If the database says you've done something bad, then you must have done something bad and it's up to you to prove that you haven't. It really shifts the burden of evidence in a way that's very contrary to the general working of liberal democracy. And then, in addition to that, there's the potential that things that aren't crimes but are private will leak out. And we tend to confuse private with secret. There's lots of stuff that's not secret but is private that becomes exposed when you have these big databases. For example, your parents did something private, otherwise you wouldn't be here. It's not a secret what they did, but it's private. It's not on the internet, unless you have extremely extraordinary parents. Everyone who went into that toilet did something private. We know what it was, but again, they don't have a glass door. There's a lot of stuff in our lives that's private, and we behave differently when our private sphere collapses. In terms of cognitive psych, I think that when we are doing stuff, we are cognitive, we think about what we're doing. When we are analytical, we're meta cognitive. We think about what we're thinking about what we're doing. And meta cognitive has its time and place as part of your overall process, but you can't be meta cognitive all the time. I don't think you can write while you're meta cognitive. If you're revising while you're writing, you just stop. It's like asking a centipede how it can walk with all those feet. It stops being able to walk because it's now thinking about how it's walking. If you want to teach someone a sport, say stickhandling in hockey, you say things like try and hit through the puck or try and be a little looser. If you say try and hold your wrist at a 45 degree angle or try and put your left skate forward and lead with your left, most of the time, the people that you're trying to teach fall apart. Coaching is all about being cognitive and not bringing people into a meta cognitive state while they're practising. When you're being watched, you're meta cognitive and there's a whole range of really important creative and daily tasks, everything from an honest conversation to just real learning, that you can't do when you're being watched. It's like trying to teach your kid how to write and looking over her shoulder while she writes the letters and going “no no no, a little steeper with the riser on that letter A, sweetie.” You can't learn to write that way. And you can't be a fully fledged citizen of a democracy that way. That's the second piece. And then the third piece is of course the risk of exposure for things that you may be marginally guilty of but that have historically been outside the import of regime. It's the equivalent of a traffic camera that issues a fine to everyone who edges one mile per hour over the limit. And the corollary of that is Cardinal Richelieu: “give me six lines of an honest man's hand and I'll find you a reason to hang him.” If you have to account for every single thing that falls into a database, it may be that there's things that you can't account for that are a mechanism to make you look guilty even if you're not guilty of anything. This is what the no-fly list has taught us, what Maher Arar has taught us. The database made him look guilty and the Americans won't take him out of the database even though he's been totally exonerated, the Americans still say that he can't fly. The building of a database state, however we conduct it, has these major risks to the common good. It needs to be really closely examined. Given that it won't secure the border, because biometrics are themselves a poor means of doing that, we need to really revisit this. And the fact that the Americans say that we need to do it... I mean, your mom had it right: if all your friends were jumping off a bridge, would you do it too? If all the other G20 nations were jumping off western democracy and landing in a boiling pit of fascism, would you jump with them? That's not a basis for good governance [shouted humorously]! Like Monty Python: Watery tarts lobbing scimitars is not a basis for good governance. That Bush says we need to do it, carried through to the Obama regime, isn't a good reason to do it in Canada.

GC: Your stock in trade is science fiction. You get to constantly imagine the world that you'd like to see. You imagine these really grim things. Some of it's beautiful, but it's pretty grim. What would you like to see in your ideal world? What would you like to see in our future?

CD: I would like to see a kind of information bill of rights that mirrored the UN declaration of human rights and that was widely accepted as kind of rote by people, where you didn't have to explain why privacy is important, why neutral networks are important. And I think if we got that, everything else becomes easier. I think that technology has this innate characteristic in that it disrupts the status quo. It's always easier to knock something down than to build it up. If you assume that both attackers and defenders have access to the same technology, which is a good assumption, then the defenders will always be at a disadvantage. That's good and bad. It's good if you want to make things better for people who the status quo have neglected historically: people of colour, people of alternate sexuality, women, kids, all those people have an advantage now that they didn't have before because they have the same organizing tools that the people who have historically tried to keep them down have access to. Only they don't have the baggage that those people have. On the other hand, it does in fact give an advantage to bad people. It gives an advantage to spyware creeps and indeed to terrorists and to people who are exploitative and to people who are human traffickers and all those other people who [mumble, 15:02]. We won't be able to take the technology out of those bad people's hands because they're criminals, so making it illegal doesn't stop them. What we can do is effectively marshal to reverse any gains they've made if people of good will can have access to the same technologies. So, my utopia, my clear eyed utopia, the utopia that I think is plausible, is one in which people of good will don't have the tools to defend themselves against people of good will taken away in the name of stopping bad things. And then we are able, people of good will, to continually organize to rebuff affronts to our dignity, to our security, to our families and so on, using those same tools. That's what I hope for. And I don't think it's an unrealistic hope.

GC: That's lovely.

CD: Thank you.

GC: So much of the world is about the status quo. You prosthelytize, well, prosthelytize is a strong word, you talk about this a lot. What do you do when you run up against people who are resistant to...

CD: Well, there are a couple of good aphorisms about the status quo. One of them is that all laws are local and no law knows how local it is. So the status quo tends to be something that's pretty new and pretty local and pretty contingent and very much honoured in the breach. Often times, you can get around people's [mumble 16:55] about changes to the status quo by pointing out that the thing that they characterize as some original, endemic state from which humanity is falling is actually like seven years old. There's a great William Gibson quote: the seventy year period during which it was possible to make money off recorded music may be at an end. It's seventy years long. It's not as though we've been selling records since the time of the bards. It's this seventy year blip. And it may be over. It doesn't mean that the music industry is over. It means that phase of the music industry's history, that tiny little seventy year blip in the music industry's history is at an end. That's one aphorism. The other is Jim Griffin's aphorism which is that if it's invented before you're eighteen, it's been there for ever. If it's invented before you're thirty, it's the greatest thing ever. And if it's invented after that it should be illegal. And it's often a matter of just helping people understand that those things they think of as having been there for ever and the greatest thing ever, it's just the latest thing in a long history of things. It's about pointing out that the Bronfmans may get to cry piracy now that they're record executives but a couple generations ago, they were drug smugglers, running rum into America during prohibition. That's how they got the money to become record executives. I'm speaking at Bronfman hall at the ROM tomorrow. I always make a point of mentioning this whenever I'm in Canada.

GC: What's the conference?

CD: It's the National Literacy Strategy.

GC: Lovely.

...

CD: I'm a UofT dropout.

GC: Aren't you also...

CD: a Waterloo and a York and a Michigan State dropout.

GC: You seem to have done all right for yourself.

CD: Who needs a degree?

GC: There's hope for the dropouts.

12 November 2009

13h15ish to 13h40ish

GC: You said a few years back that you couldn't move back to Canada because of the bad internet

CD: It's getting pretty bad in England. It's certainly pretty bad here.

GC: The CRTC just came down with a ruling on traffic shaping...

CD: Which was basically:you can only do terrible, immoral things in a limited way that we may police if we decide to. Yeah. It was a pretty awful ruling. I think the CRTC is generally asleep at the switch. I mean, the media consolidation in this country has been just disgraceful. So yeah, I'm pretty unimpressed with the CRTC as a regulator. The sheer amount of consolidation, both in media and telecoms and the cross consolidation between media and telecoms has been I think a total policy disaster for Canada. Canada's really lagging in the OECD in access, speed, cost and equality. They keep trying to redefine what broadband is in order to make us look better on the OECD stats. It's broadband if you can download a jpeg in less than a minute. This is not broadband. Broadband is Korean standard: 100MB. And up.

GC:Everyone's really proud of 21MB right now. On the whole 21MB thing, have you heard about this new thing Bell is doing? The turbostick? It's pretty awful. They're going for mobile internet, with a 500MB a month cap.

CD: I think the thing about caps is first of all, it's hard to imagine any other industrial sector that would say “there's a lot of demand for our product, how can we reduce it?” I think on the one hand, this represents a kind of failure of entrepreneurial imagination that's only possible where you have these monopolistic, badly regulated industries. The other thing about caps is what it does to network behaviour, network use. It punishes experimentation because you have to ration your network use. What this does is it undermines entrepreneurship. If you want to start a new Canadian networked business, your capacity to lure customers into your business is undermined by the fact that any customer who clicks on your web page will reduce their remaining bytes for the month. And bytes per month is a really hard measure for the average user, or even a sophisticated user to get their head around. Do you know how many bytes are in a web page before you click it? Or after you click it? We have a very hard time predicting the amount of bits that we have. So it's very hard to contain our use. So we would become even more conservative of our use. As a piece of national industrial policy, if you want to encourage the greatest amount of entrepreneurial activity on the network, the greatest amount of civic participation... Say you're planning for a pandemic swine flu outbreak and you want to produce a bunch of high quality health videos that will help people adequately prepare for the pandemic, do you really want people going “Well, I can spend my bits this month, my allowance, on looking at that health information, or I can spend it on downloading my banking information and I have to make that trade off, or I'm either going to get cut off or hit with some incredibly high overage fee.” Do you really want people making that decision? Is that good national policy? It would be different if the phone and cable companies were not subject to such enormous public subsidy. But they are. First of all, in the case of the phone companies, they got an enormous public subsidy in the fact that they exist at all. All that wire was laid with public expense. But everybody gets public subsidy in the use of the airwaves, in the use of rights of way, they essentially have de facto monopolies. I feel like the CRTC should say “If you don't want to allow a free and open network on these wires, that's your business. We'll either buy them from you at the scrap value of this copper, or you can take them out of our ground and we'll find someone else who'll run those wires. Somewhere out there, there's an entrepreneur who wants to provide the network that Canada deserves. If it's not you, that's fine. We'll have a competitive market. We'll have these guys who want to provide the network that Canadians want and you can provide the network that you think Canadians want. And if you're right and we're wrong, then Canadians will buy your service. But for so long as you're a regulatory monopoly, you have to act in the public interest.”

GC: Actually, how is it in the UK?

CD: It's not great. In general, the quality of governance in the UK is very poor. Partly because the political left has shifted so far to the right that there really isn't... I mean, I support the Lib Dems kind of generally because they're the only party that doesn't expect me to carry a biometric identity card. But as a left wing opposition goes, they're not very powerful and they're not very left wing. Labour, who are traditionally supposed to be the voice of the left, have shifted so far to the right that I think that they're... well... they're Bushites. Right? They went to war in Iraq. They are Bushites. Their policies are in line with those of George Bush. Including policies on civil liberties and so on. As a kind of microcosm of that, the network policy, the information policy is very poor. The government has been really reluctant to release information about its own operation. Quasi-governmental entities like the BBC are arguing for the right to put DRM on their broadcasts even though not only do they get public airwaves, but they get something like six or seven billion pounds a year out of the public's hands from the license fee, by governmental enforcement. It's really unseemly that they would argue for the right to DRM their signal. And now we have the copyright enforcement stuff. On one hand, you've got the anti-terrorism people saying that ISPs should be required to monitor and store all communications. That's also happening on the European level. Then you have the database nation where they're saying that we need, if not a national identity card, then a series of linked national databases that do the equivalent of a national identity card. And then finally, they're saying that we're going to have a three strikes regime where if anyone in your household is accused without evidence or conviction of three acts of copyright infringement you lose your network access and your name goes on a national register of people to whom it's illegal to supply internet access. This is really a dreadful piece of policy. I happen to live there and it's unlikely that I'm going to be moving away any time soon just for sheer inertia and the fact that my wife has a very good job, but they've got lots of network caps, they've got crummy networking policies. BT, who are the equivalent of Bell, really, in terms of being a legacy former national monopoly. BT got done for using something called Phorm, P-H-O-R-M, which I think may have had limited deployments here and in the U.S., I forget where. Initially, what they did was install Phorm as a piece of spyware on your computer without your permission. And what it did was inserted ads based on a tracking of every click you made on every page you visited. And then after they were told they can't install spyware on your computer without your knowledge, they went back and redid it as a piece of network middleware that tracks every click and does dynamic page rewriting again with these targeted ads. It's a revolting way of running a network. They're running it as an opt-out service. There's a huge amount of tracking that they're doing, a huge amount of monkeying with your network connection. It's very bad.

GC: You mentioned biometric ID cards. Of course, that's a pretty hot topic here right now because, of course, the border provinces need to comply with the U.S. Ontario is trying to roll out EDLs...

CD: Biometrics are an incredibly bad idea as a security measure. Partly because any good security token needs to be revokable in the event that it leaks. You need to be able to change your PIN if someone finds your PIN. You need to be able to get a new credit card number if your credit card number leaks onto the internet. What do you do if your finger prints leak? Right? And fingerprints leak like crazy. How many surfaces do you think you left your fingerprints on today? As a great example of this, the Chaos Computer Club lifted the fingerprints of the German chancellor, who was responsible for pushing for biometrics in that country, and made ten thousand copies of them on acetate, which would work in most fingerprint readers and widely distributed them. As a security metric, these are very very poor. And to the extent that we actually believe that we need security at the border, we should have good security, not bad security. That's one really important piece of it. But you know, the general linking of multiple databases, first of all, creates a false sense of security or certainty among the people who run those databases. There's a tendency to believe the database over reality. So if they say “well, the database says you were here and then here,” it's very hard to prove otherwise. The database becomes its own proof. And we know that those databases are very flawed and the more we link them, the more flawed they become. So there's that risk. In terms of Terry Gilliam's Brazil, it's the Tuttle-Buttle risk. If the database says you've done something bad, then you must have done something bad and it's up to you to prove that you haven't. It really shifts the burden of evidence in a way that's very contrary to the general working of liberal democracy. And then, in addition to that, there's the potential that things that aren't crimes but are private will leak out. And we tend to confuse private with secret. There's lots of stuff that's not secret but is private that becomes exposed when you have these big databases. For example, your parents did something private, otherwise you wouldn't be here. It's not a secret what they did, but it's private. It's not on the internet, unless you have extremely extraordinary parents. Everyone who went into that toilet did something private. We know what it was, but again, they don't have a glass door. There's a lot of stuff in our lives that's private, and we behave differently when our private sphere collapses. In terms of cognitive psych, I think that when we are doing stuff, we are cognitive, we think about what we're doing. When we are analytical, we're meta cognitive. We think about what we're thinking about what we're doing. And meta cognitive has its time and place as part of your overall process, but you can't be meta cognitive all the time. I don't think you can write while you're meta cognitive. If you're revising while you're writing, you just stop. It's like asking a centipede how it can walk with all those feet. It stops being able to walk because it's now thinking about how it's walking. If you want to teach someone a sport, say stickhandling in hockey, you say things like try and hit through the puck or try and be a little looser. If you say try and hold your wrist at a 45 degree angle or try and put your left skate forward and lead with your left, most of the time, the people that you're trying to teach fall apart. Coaching is all about being cognitive and not bringing people into a meta cognitive state while they're practising. When you're being watched, you're meta cognitive and there's a whole range of really important creative and daily tasks, everything from an honest conversation to just real learning, that you can't do when you're being watched. It's like trying to teach your kid how to write and looking over her shoulder while she writes the letters and going “no no no, a little steeper with the riser on that letter A, sweetie.” You can't learn to write that way. And you can't be a fully fledged citizen of a democracy that way. That's the second piece. And then the third piece is of course the risk of exposure for things that you may be marginally guilty of but that have historically been outside the import of regime. It's the equivalent of a traffic camera that issues a fine to everyone who edges one mile per hour over the limit. And the corollary of that is Cardinal Richelieu: “give me six lines of an honest man's hand and I'll find you a reason to hang him.” If you have to account for every single thing that falls into a database, it may be that there's things that you can't account for that are a mechanism to make you look guilty even if you're not guilty of anything. This is what the no-fly list has taught us, what Maher Arar has taught us. The database made him look guilty and the Americans won't take him out of the database even though he's been totally exonerated, the Americans still say that he can't fly. The building of a database state, however we conduct it, has these major risks to the common good. It needs to be really closely examined. Given that it won't secure the border, because biometrics are themselves a poor means of doing that, we need to really revisit this. And the fact that the Americans say that we need to do it... I mean, your mom had it right: if all your friends were jumping off a bridge, would you do it too? If all the other G20 nations were jumping off western democracy and landing in a boiling pit of fascism, would you jump with them? That's not a basis for good governance [shouted humorously]! Like Monty Python: Watery tarts lobbing scimitars is not a basis for good governance. That Bush says we need to do it, carried through to the Obama regime, isn't a good reason to do it in Canada.

GC: Your stock in trade is science fiction. You get to constantly imagine the world that you'd like to see. You imagine these really grim things. Some of it's beautiful, but it's pretty grim. What would you like to see in your ideal world? What would you like to see in our future?

CD: I would like to see a kind of information bill of rights that mirrored the UN declaration of human rights and that was widely accepted as kind of rote by people, where you didn't have to explain why privacy is important, why neutral networks are important. And I think if we got that, everything else becomes easier. I think that technology has this innate characteristic in that it disrupts the status quo. It's always easier to knock something down than to build it up. If you assume that both attackers and defenders have access to the same technology, which is a good assumption, then the defenders will always be at a disadvantage. That's good and bad. It's good if you want to make things better for people who the status quo have neglected historically: people of colour, people of alternate sexuality, women, kids, all those people have an advantage now that they didn't have before because they have the same organizing tools that the people who have historically tried to keep them down have access to. Only they don't have the baggage that those people have. On the other hand, it does in fact give an advantage to bad people. It gives an advantage to spyware creeps and indeed to terrorists and to people who are exploitative and to people who are human traffickers and all those other people who [mumble, 15:02]. We won't be able to take the technology out of those bad people's hands because they're criminals, so making it illegal doesn't stop them. What we can do is effectively marshal to reverse any gains they've made if people of good will can have access to the same technologies. So, my utopia, my clear eyed utopia, the utopia that I think is plausible, is one in which people of good will don't have the tools to defend themselves against people of good will taken away in the name of stopping bad things. And then we are able, people of good will, to continually organize to rebuff affronts to our dignity, to our security, to our families and so on, using those same tools. That's what I hope for. And I don't think it's an unrealistic hope.

GC: That's lovely.

CD: Thank you.

GC: So much of the world is about the status quo. You prosthelytize, well, prosthelytize is a strong word, you talk about this a lot. What do you do when you run up against people who are resistant to...

CD: Well, there are a couple of good aphorisms about the status quo. One of them is that all laws are local and no law knows how local it is. So the status quo tends to be something that's pretty new and pretty local and pretty contingent and very much honoured in the breach. Often times, you can get around people's [mumble 16:55] about changes to the status quo by pointing out that the thing that they characterize as some original, endemic state from which humanity is falling is actually like seven years old. There's a great William Gibson quote: the seventy year period during which it was possible to make money off recorded music may be at an end. It's seventy years long. It's not as though we've been selling records since the time of the bards. It's this seventy year blip. And it may be over. It doesn't mean that the music industry is over. It means that phase of the music industry's history, that tiny little seventy year blip in the music industry's history is at an end. That's one aphorism. The other is Jim Griffin's aphorism which is that if it's invented before you're eighteen, it's been there for ever. If it's invented before you're thirty, it's the greatest thing ever. And if it's invented after that it should be illegal. And it's often a matter of just helping people understand that those things they think of as having been there for ever and the greatest thing ever, it's just the latest thing in a long history of things. It's about pointing out that the Bronfmans may get to cry piracy now that they're record executives but a couple generations ago, they were drug smugglers, running rum into America during prohibition. That's how they got the money to become record executives. I'm speaking at Bronfman hall at the ROM tomorrow. I always make a point of mentioning this whenever I'm in Canada.

GC: What's the conference?

CD: It's the National Literacy Strategy.

GC: Lovely.

...

CD: I'm a UofT dropout.

GC: Aren't you also...

CD: a Waterloo and a York and a Michigan State dropout.

GC: You seem to have done all right for yourself.

CD: Who needs a degree?

GC: There's hope for the dropouts.

I had a bit of a revelation this morning. As we know, purist hipsters, by nature, eschew anything particularly popular or common. They favour, instead, the obscure and unique. This is why they can be spotted at craft fairs and seconds hand stores. This means that hipsters must take precautions to avoid mall brand clothing, clothing from popular, mainstream retailers.

But what if a hipster, for some reason, finds him/herself desiring, for whatever reason, a mall brand garment? Purchasing something common and popular goes against the grain. In order to maintain status, the purchase must be hidden or downplayed. But there is a solution.

Most manufacturers maintain outlet stores. These outlet stores are stocked with leftovers, unsuccessful garments, items from previous seasons and the holy grail: samples. Samples fit the hipster bill beautifully. They're generally one of a kind, or at least incredibly uncommon. They have entertaining idiosyncrasies. They epitomize process and experimentation. Most importantly, they cannot be found in malls. Thus, a hipster with the desire to purchase mall brand clothes may safely wear samples, secure in the knowledge that the garment is not only unique, but also has a story (however short) to go with it.

But what if a hipster, for some reason, finds him/herself desiring, for whatever reason, a mall brand garment? Purchasing something common and popular goes against the grain. In order to maintain status, the purchase must be hidden or downplayed. But there is a solution.

Most manufacturers maintain outlet stores. These outlet stores are stocked with leftovers, unsuccessful garments, items from previous seasons and the holy grail: samples. Samples fit the hipster bill beautifully. They're generally one of a kind, or at least incredibly uncommon. They have entertaining idiosyncrasies. They epitomize process and experimentation. Most importantly, they cannot be found in malls. Thus, a hipster with the desire to purchase mall brand clothes may safely wear samples, secure in the knowledge that the garment is not only unique, but also has a story (however short) to go with it.

The good folks at Constant are at it again. The Verbindingen/Jonctions 12 festival is coming up, with the theme "By data we mean." Among all the activities slated to take place, there's also going to be a fine array of artwork on display. Our favourite robot sleuth, Lawbot along with Copycat and the leader of The Cabal are going to be in attendance in their fine, digital, text based form. If you're in Brussels between November 21 and 29, be sure to check out what Constant is offering up.

Just got a load of postcards back from the printer. I, for one, am pretty happy with them. They'll be making an appearance this weekend at Expozine. There's a pigeon, a hightop running shoe, the island of Montreal and Jean Drapeau. Not necessarily in that order.

Because I've yet to kick the habit of drawing Concordia buildings, here's another: the Hall building as panopticon (okay, so it isn't actually a real panopticon, given that it's only looking in one direction, but I couldn't resist calling it Panopticoncordia).

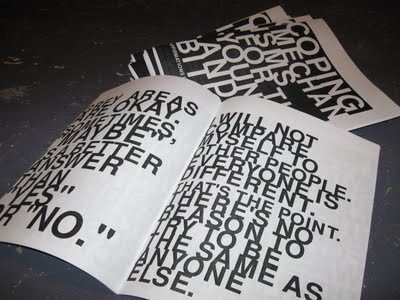

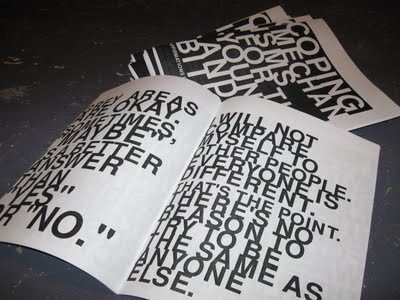

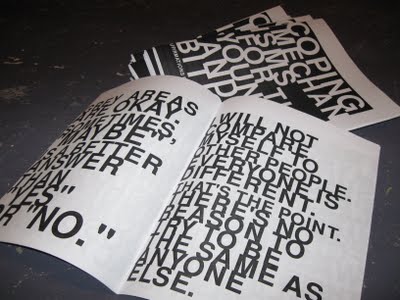

Just over a year ago, I posted what I called "A Manifesto for ginger coons." Much of the text of that manifesto is back, in the form of a zine. Now, however, it's called Coping Mechanisms for the Young and Ambitious. Just in time for Expozine next weekend. Photos below.

Setting up an account with any web service provider means a lot. It means agreeing to terms of service, buying into their framework, playing their game. These services are not provided for free for the benefit of humankind. They serve ads and gain revenue. Some of them sell personal information to third parties. At the very least, when you sign up for a free web service, you enter into a legal agreement with another entity and also into a business relationship, wherein you allow them to sell your attention to others. While most people don't view it as a choice, it is. And it is an individual choice. It should be made, in an informed way, by an individual, without coercion.

Educational institutions decide what their students will learn and which tools they'll use in order to learn. Traditionally, this has meant deciding which textbooks and articles will be read. As any educator bombarded with textbook samples knows, this is not a strictly academic decision, but one with profound financial implications for many different stakeholders. It is in the power of the educator to decide which textbook all her students will have to purchase.

Increasingly, the tools of education are more than just textbooks. The new tools include courseware and software. Academic institutions decide whether to tie their students to Blackboard, Moodle or any other courseware system. What's more, those institutions decide how zealous they will be about the enforcement of their courseware standards. Will they allow one faculty/department/professor to diverge from the norm?

The issue, of course, goes far deeper than courseware. And this is where we come back to the initial discussion of free web services. Educators in less zealous institutions may choose to abandon standard courseware in favour of a third party solution, often a service already favoured by students. A professor may, for example, choose to conduct course discussions in a Facebook group devoted to the class. This decision presents problems. Sure, most students are probably already Facebook users. But it can't be taken for granted that they all are. And what of those who don't already use the service? In order to engage with the class, these students are forced to enter into a legal and (effectively) financial agreement with a third party service provider. And if they don't, they lose out. That dynamic smacks of coercion.

I don't mean to be negative. I am, in fact, all for the idea of using accessible, available, ostensibly free tools with which students are already comfortable. But it bears thinking about. In an attempt to make learning accessible and integrative, an important element of choice may be lost.

Educational institutions decide what their students will learn and which tools they'll use in order to learn. Traditionally, this has meant deciding which textbooks and articles will be read. As any educator bombarded with textbook samples knows, this is not a strictly academic decision, but one with profound financial implications for many different stakeholders. It is in the power of the educator to decide which textbook all her students will have to purchase.

Increasingly, the tools of education are more than just textbooks. The new tools include courseware and software. Academic institutions decide whether to tie their students to Blackboard, Moodle or any other courseware system. What's more, those institutions decide how zealous they will be about the enforcement of their courseware standards. Will they allow one faculty/department/professor to diverge from the norm?

The issue, of course, goes far deeper than courseware. And this is where we come back to the initial discussion of free web services. Educators in less zealous institutions may choose to abandon standard courseware in favour of a third party solution, often a service already favoured by students. A professor may, for example, choose to conduct course discussions in a Facebook group devoted to the class. This decision presents problems. Sure, most students are probably already Facebook users. But it can't be taken for granted that they all are. And what of those who don't already use the service? In order to engage with the class, these students are forced to enter into a legal and (effectively) financial agreement with a third party service provider. And if they don't, they lose out. That dynamic smacks of coercion.

I don't mean to be negative. I am, in fact, all for the idea of using accessible, available, ostensibly free tools with which students are already comfortable. But it bears thinking about. In an attempt to make learning accessible and integrative, an important element of choice may be lost.

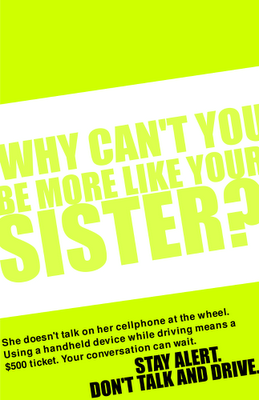

Ontario has some new legislation meant to penalize people who talk on handsets while driving. The two groups most likely to talk and drive are young people and taxi drivers. So, in the fine tradition of alarming and mean public service announcements meant to scare people into compliance, I've made a couple posters.